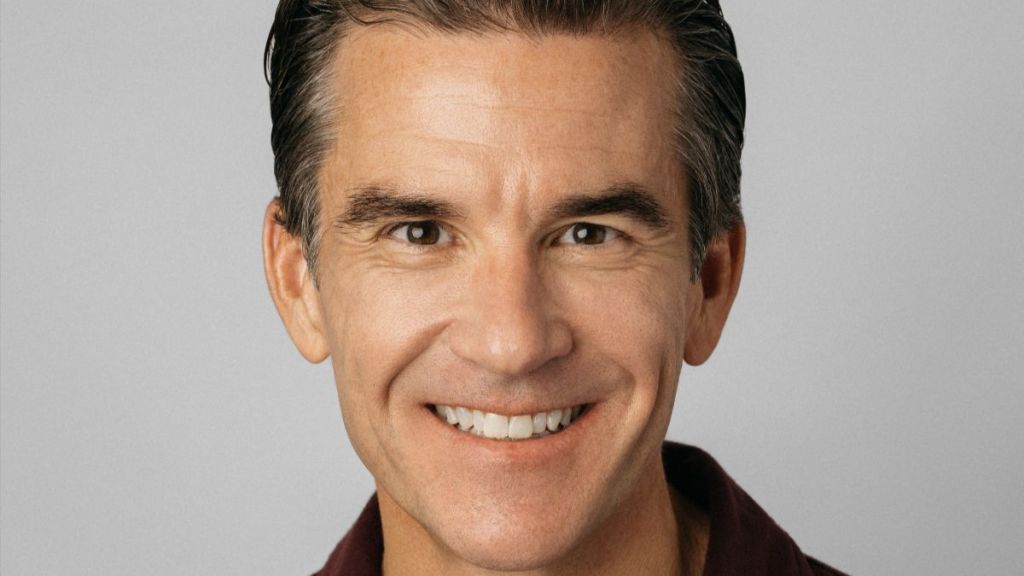

Ryan McGuigan’s story sounds like a TV show, so maybe it’s fitting that he’s working on one. Law is the family business, and Ryan built up a successful career as an attorney. He also founded Second Chance Interventions to make a difference in the world of addiction recovery. Yet Ryan got bit by the acting bug early on, and is still pursuing his passions of acting and writing. How exactly do all these things coexist?

In a wide-ranging interview, Ryan spoke about his journey from being an actor to becoming an attorney, and how he’s come full circle. He also teased the TV project that he’s working on with Tulsa King‘s Terence Winter. But most importantly, he gave his perspective on how society perceives addiction, and how people can help.

Brittany Frederick: To say that your career trajectory has been unconventional would be an understatement. Which came first, the law or the entertainment career?

Ryan McGuigan: My dad was the chief prosecutor of the state of Connecticut, so the law was sort of a family business. And then when I was I think about four or five, I was asked by one of my neighbors who was into theater to be in The King and I. I went to Hartford Stage, and I was on for just a couple of weekends as one of the younger sons, and I caught sort of a bug with applause… It really was addicting, and I loved it.

I started to do repertory theater in my local town, and then I did theater in school—elementary school and middle school, and then I ended up going to a boarding school with a very good fine arts program. I continued to act in theater in college, and then I went off to Ireland. I finished school in Cork, which is located in Southern Ireland. And there I was lucky enough to be in a play that won a substantial number of awards. We were able to travel all throughout Europe with the play. So that was very exciting. I came home and decided that forget the law, I wanted to be an actor—and that did not go over well with the family business. A lot of my financial support for my artistic hobby dried up.

How did you pivot to the law, and then within that, you’ve worked in different roles in the legal profession?

I went to New York City, and I was able to cobble together a compromise, which was I would go to law school while I lived in New York City and tried to make it as an actor. So I tried to do two things at once. It almost worked out. (Laughs.) I was able to get into a few plays in the city, and then finally got into one at the Irish Arts Center which was very successful, and I got a lot of praise in [the] New York Times, the New York Post. I thought that I was on my way and then quickly found out that’s just the beginning.

Life kind of got in the way. I ended up getting married, and from then on, it was a decision to sort of grow up. And when I was told to grow up, that was to now take your legal degree and go be a lawyer. I didn’t want to work for the family business, so I became a prosecutor… My idea was that I could be a prosecutor and have a real job, but I could still sort of pursue acting on the side… I didn’t do either one very well, and so just gave up on the acting for for a long time.

I was a prosecutor for many, many years. And my first wife decided when we had children that she wanted to be a stay at home mom. I think I was making $54,000 a year as a prosecutor back then, so that just wasn’t going to cut it. So then I joined the family business, which brought me into a different world of crime.

It brought me into a world that was covered very deeply by the entertainment field, and that would be the world of the mafia. I had a very famous case with the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, which got me involved with a film on Netflix, which then got me involved with a production that’s being produced by Terence Winter, which I’m very lucky to be a principal actor on and a writer for. I’m in the writers’ room for the production, which is called Federal Hill. So hopefully you’ll see that within the next year.

Before we get into that, you’ve established Second Chance interventions, and addiction is also something that’s covered a lot in the media—both in news and scripted drama. What do you think is the biggest misconception between what we see on the subject, and the reality?

Who is affected by addiction. When we look at our phones and we look at the television and we talk to people, usually it’s “Oh, those poor, homeless people,” and they’re suffering from from addiction. There’s people in the inner city, and they’re suffering from addiction. My sister was a physician’s assistant and died of an overdose. So many of my friends and colleagues and people that have mentored me over the years have been afflicted by addiction.

The biggest misconception that I see with the public is that there’s a difference with what you’re addicted to. And there really isn’t. In the United States we’re going to have, each year, about 100,000 excess deaths due to opiates. Every year, the amount of of excess deaths due to direct and collateral consequences of alcohol addiction are there… It’s around 350 to 380,000 per year, and that’s more than triple [that].

As an Irish kid growing up, we didn’t have a single social event that didn’t have alcohol with it… and so it was sort of ingrained in me that that alcohol was part of family celebrations. It was part of good times, and it was a part of being a man. And so I think that the biggest misconception with addiction is which, if any, addiction is worse than the other. There really isn’t any.

How can people better educate themselves on addiction, or find more support for themselves or their loved ones who are dealing with it? Are there specific resources you would recommend based on your experience?

If you’re the family member of people who are suffering from addiction, substance use disorder, you can go to any Al-Anon meeting in your area…You’ll find not only a wealth of information, but also a wealth of support. To deal with a an individual, especially a loved one, that is suffering from substance use disorder, there are so many emotions that it’s very difficult to find the right path. And a lot of times, our instincts are part of how that person got into where they are in the first place. Many, many times I see people struggling with boundaries and struggling with consequences.

We all have to remember that the person suffering from the substance use disorder is not going to function rationally, because they’re not rational. And so it’s up to the loved ones and friends to make better choices on that person’s behalf. Ultimately, you have to get that person to want to live a different way. And the most difficult part of doing that is making the way that they’ve been living impossible for them.

Those are the most difficult decisions to make, and you need support for it. I do know clients, family members who have benefited greatly from going to Al Anon meetings and getting that moral support from people who will say this does work; you’ve just got to stick to it. And so I think that that’s probably the best resource.

How do you handle that tonal shift in your day to day? To be dealing with serious, sometimes life and death subjects as an attorney and in your intervention work, but then changing gears to the creative side of your career?

I deal with it with humor a lot. I just say, you know, I’ve been going a lot more funerals than than we have weddings lately—and that’s the truth. And if you think about it that way, it’s very dark, and it’s very heavy. In my criminal work, I deal with a lot of a lot of dark subjects, and I always tell myself, that’s why I get paid to do that. On the other side, with the addiction stuff… there’s a lot more satisfaction with that.

The trouble with it is, that for every success that I might have, I would say at least half of the people that I see stumble back at some point to to to addiction. And that’s to be expected. Part of recovery is relapse. It’s just with opiates, it can be immediate, and the consequences of it can be immediate and they can be ultimate, which is another funeral to go to.

You have this creative outlet in your life with the acting and the writing. To circle back to Federal Hill, what can you say about that project and getting to work with someone of the caliber of Terence Winter?

it’s an honor. I learn a lot. The show is written by Michael Corrente, so he’s the showrunner on it, and the creator. There is, however, sort of a professional expectation. Because I had gotten involved with these guys through working on [the Netflix project] This Is a Robbery; that was my original introduction to them. And then I had written a script right around that same time.

It was during COVID, and my wife wanted to watch a movie. We were scrolling through movies and she said, there’s nothing that I really want to watch. It’s really boring. How come somebody can’t write a fun movie, like back in the ’80s? I said you know what, I’ll write an 80s movie for you. My roommate from boarding school is the showrunner on Family Guy, and I have a couple of other friends from school who are screenwriters out in L.A., so I got a couple of scripts from them, and I took a look at [them], and I’m like, “Yeah, I can probably do this.” I wrote a script, and it got through the quarterfinals at a screenwriters’ contest brought on by the the Academy Awards.

It ended up with Michael Corrente, and he was working with Terrence; they had done Brooklyn Rules together, and I believe that Michael had directed an episode or two of Boardwalk Empire. And then a few of my friends from when I used to work with the Irish Arts Center also worked with Terry on Boardwalk Empire. So it’s kind of like come full circle with some of these people that I know… When I work with those guys, I learned so much more in 10 minutes than I would with 10 months of research on my own, because they work at such a pace that it’s eye-opening, and it’s commendable. It just fills me with awe and also joy, because I really, really love working with them.

Has there ever been any crossover between the two in terms of process? Do you have to change the way you work based on what you’re working on, or do the habits from one profession serve you in the other?

It’s the same thing—it’s telling a believable story. I do write true crime and the fictionalized portion of it, what I’m constantly worried about [is] I’m stuck with history. [Federal Hill is] about the mafia in the United States from about November of 1963 until June of 1968. It begins with the death of John F. Kennedy, and it ends with the death of Robert F. Kennedy. And so when I’m writing Federal Hill, I know that I have history as sort of a guardrail, and I can’t stray from that. That keeps me grounded in reality, because the reality is already created. All you’re doing is putting dialogue to something that happened and then trying to make connections between one thing and the other thing.

When I write fiction, I kind of have to create those guardrails of this is the universe that I’m writing in, and that it does have rules… Somebody will say, can you write me a scene about a prison break? I go yeah, I can, because I know a lot about prisons. And they’ll say well, can you write me a scene about a bunch of guys skydiving over Alaska into a volcano? I go no, I’ve never done that, and so I don’t know. I can fictionalize only so much, as long as I have experience with it. My process is, I have to imagine sort of the complete story from pillar to post within that universe, and everything has to obey the rules of the universe.

In law, it’s kind of the same thing. I’m confined to the law itself, and those are my guardrails, and then I’ve got to weave a story that makes sense to 12 people that are sitting in a box over here, because they’re critical viewers. They’re like film critics, and they’re going to criticize the story that you’re presenting. The state is going to present a story and they’re going to say, this is what the facts lay out. This is what the evidence means. I have to take the same exact facts and sort of rework them into a way that it doesn’t mean that it should conclude what that guy says. You should conclude something completely different, or you should say there is no real conclusion within this universe of rules and law. Essentially it’s the same thing, which is constructing a believable story that people can relate to.

For more information on Ryan’s work, visit Second Chance Interventions. Photo Credit: Photographer not listed/Provided by Abigail Public Relations.

Article content is (c)2020-2026 Brittany Frederick and may not be excerpted or reproduced without express written permission by the author. Follow me on Twitter at @BFTVTwtr and on Instagram at @BFTVGram. For story pitches, contact me at tvbrittanyf@yahoo.com.